The Cosmology of the Bhagavata Purana

Richard L. Thompson

An Overview

Richard L. Thompson

An Overview

The inquisitive human mind naturally yearns to understand the universe and man’s place within it. Today scientists rely on powerful telescopes and sophisticated computers to formulate cosmological theories. In former times, people got their information from traditional books of wisdom. Followers of India’s ancient culture, for example, learned about the cosmos from scriptures like the Srimad-Bhagavatam, or Bhagavata Purana. But the Bhagavatam’s descriptions of the universe often baffle modern students of Vedic literature. Here Bhaktivedanta Institute scientist Dr. Richard Thompson suggests a framework for understanding the Bhagavatam’s descriptions that squares with our experience and modern discoveries.

Figure 2 The Bhagavatam Picture at First Glance

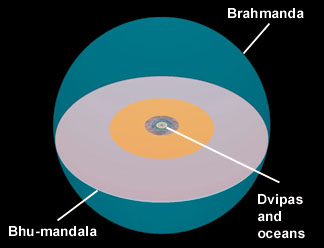

The region within the shell (Figure 3) is called the Brahmanda, or "Brahma egg." It contains an earth disk or plane—called Bhu-mandala—that divides it into an upper, heavenly half and a subterranean half, filled with water. Bhu-mandala is divided into a series of geographic features, traditionally called dvipas, or "islands," varshas, or "regions," and oceans.

In India such globes exist. In the example shown here (Figure 7), the land area between the equator and the mountain arc is Bharata-varsha, corresponding to greater India. India is well represented, but apart from a few references to neighboring places, this globe does not give a realistic map of the Earth. Its purpose was astronomical, rather than geographical.

When one structure is used to represent several things in a composite map, there are bound to be contradictions. But these do not cause a problem if we understand the underlying intent. We can draw a parallel with medieval paintings portraying several parts of a story in one composition. For example, Masaccio’s painting "The Tribute Money" (Figure 1) shows Saint Peter in three parts of a Biblical story. We see him taking a coin from a fish, speaking to Jesus, and paying a tax collector. From a literal standpoint it is contradictory to have Saint Peter doing three things at once, yet each phase of the Biblical story makes sense in its own context.

When one structure is used to represent several things in a composite map, there are bound to be contradictions. But these do not cause a problem if we understand the underlying intent. We can draw a parallel with medieval paintings portraying several parts of a story in one composition. For example, Masaccio’s painting "The Tribute Money" (Figure 1) shows Saint Peter in three parts of a Biblical story. We see him taking a coin from a fish, speaking to Jesus, and paying a tax collector. From a literal standpoint it is contradictory to have Saint Peter doing three things at once, yet each phase of the Biblical story makes sense in its own context.

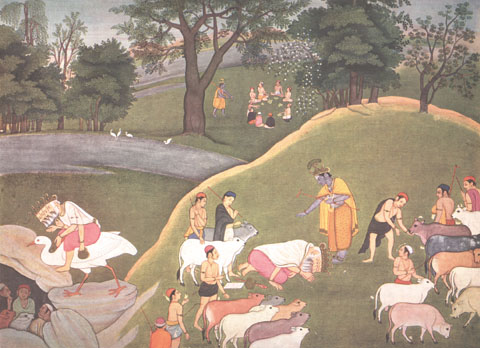

A similar painting from India (Figure 2) shows three parts of a story about Krishna. Such paintings contain apparent contradictions, such as images of one character in different places, but a person who understands the story line will not be disturbed by this. The same is true of the Bhagavatam, which uses one model to represent

different features of the cosmos.

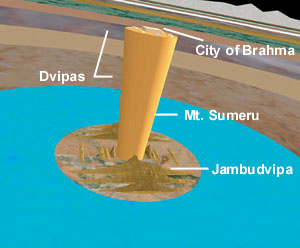

In the center of Bhu-mandala (Figure 4) is the circular "island" of Jambudvipa, with nine varsha subdivisions. These include Bharata-varsha, which can be understood in one sense as India and in another as the total area

inhabited by human beings. In the center of Jambudvipa stands the cone-shaped Sumeru Mountain, which represents the world axis and is surmounted by the city of Brahma, the universal creator.

To any modern, educated person, this sounds like science fiction. But is it? Let’s consider the four ways of seeing the Bhagavatam’s descriptions of the Bhu-mandala.

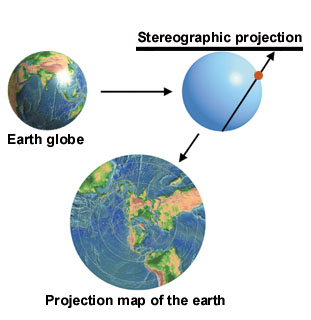

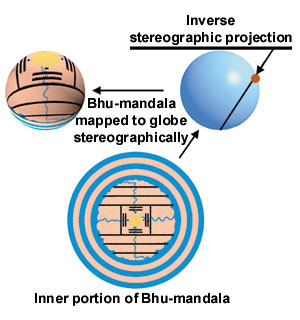

We begin by discussing the interpretation of Bhu-mandala as a planisphere, or a polar-projection map of the Earth globe. This is the first model given by the Bhagavatam. A stereographic projection is an ancient method of mapping points on the surface of a sphere to points on a plane. We can use this method to map a modern Earth globe onto a plane, and the resulting flat projection is called a planisphere (Figure 5). We can likewise view Bhu-mandala as a stereographic projection of a globe (Figure 6).

![]()

(1) Bhu-mandala as a Polar Projection of the Earth Globe

Although the Bhagavatam doesn’t explicitly describe the Earth as a globe, it does so indirectly. For example, it points out that night prevails diametrically opposite to a point where it is day. Likewise, the sun sets at a point opposite where it rises. Therefore, the Bhagavatam does not present the naive view that the Earth is flat.

We can compare Bhu-mandala with an astronomical instrument called an astrolabe, popular in the Middle Ages. On the astrolabe, an off-centered circle represents the orbit of the sun—the ecliptic. The Earth is represented in stereographic projection on a flat plate, called the mater. The ecliptic circle and important stars are represented on another plate, called the rete. Different planetary orbits could likewise be represented by different plates, and these would be seen projected onto the Earth plate when one looks down on the instrument.

The Bhagavatam similarly presents the orbits of the sun, the moon, planets, and important stars on a series of planes parallel to Bhu-mandala.

Seeing Bhu-mandala as a polar projection is one example of how it doesn’t represent a flat Earth.

| (2) Bhu-mandala as a Map of the Solar System |

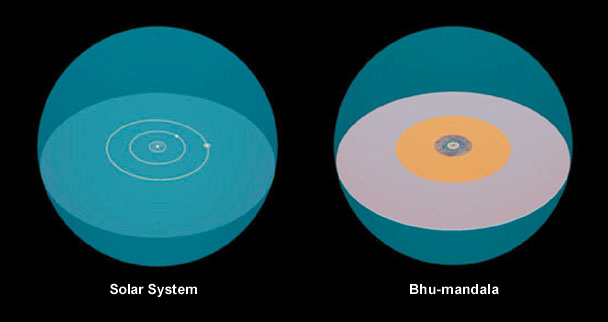

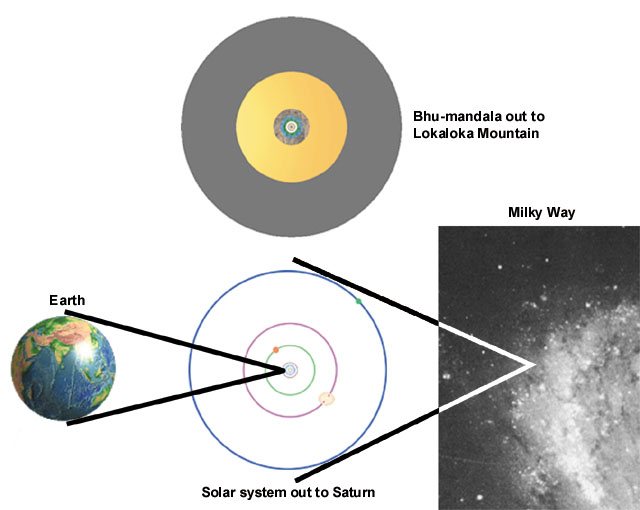

One striking feature of the Bhagavatam’s descriptions has to do with size. If we compare Bhu-mandala with the Earth, the solar system out to Saturn, and the Milky Way galaxy, Bhu-mandala matches the solar system closely, while radically differing in size from Earth and the galaxy.

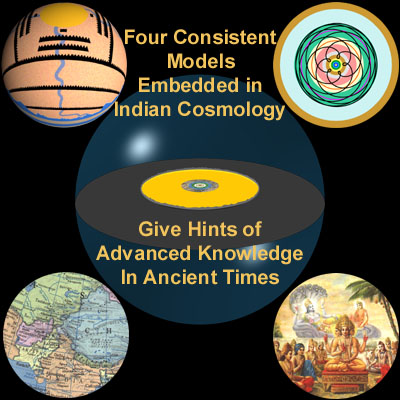

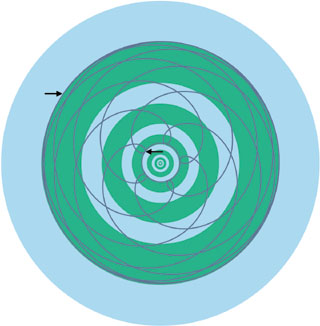

Furthermore, the structures of Bhu-mandala correspond with the planetary orbits of the solar system (Figure 9).

Figure 10

If we compare the rings of Bhu-mandala with the orbits of Mercury, Venus (Figure 10), Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, we find several close alignments that give weight to the hypothesis that Bhu-mandala was deliberately designed as a map of the solar system.

If we compare the rings of Bhu-mandala with the orbits of Mercury, Venus (Figure 10), Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, we find several close alignments that give weight to the hypothesis that Bhu-mandala was deliberately designed as a map of the solar system.

Until recent times, astronomers generally underestimated the distance from the earth to the sun. In particular, Claudius Ptolemy, the greatest astronomer of classical antiquity, seriously underestimated the Earth-sun distance and the size of the solar system. It is remarkable, therefore, that the dimensions of Bhu-mandala in the Bhagavatam are consistent with modern data on the size of the sun’s orbit and the solar system as a whole.

[See BTG, Nov./Dec. 1997.]

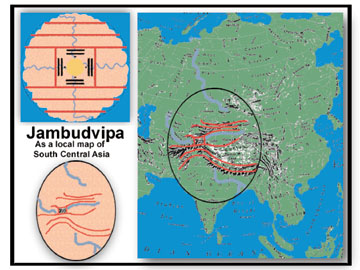

| (3) Jambudvipa as a Topographical Map of South-Central Asia |

Figure 11

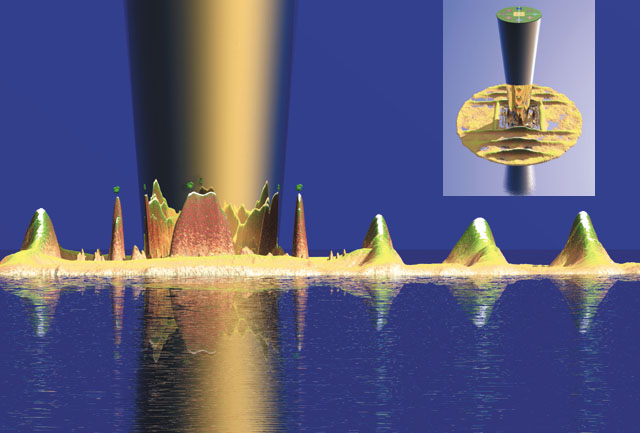

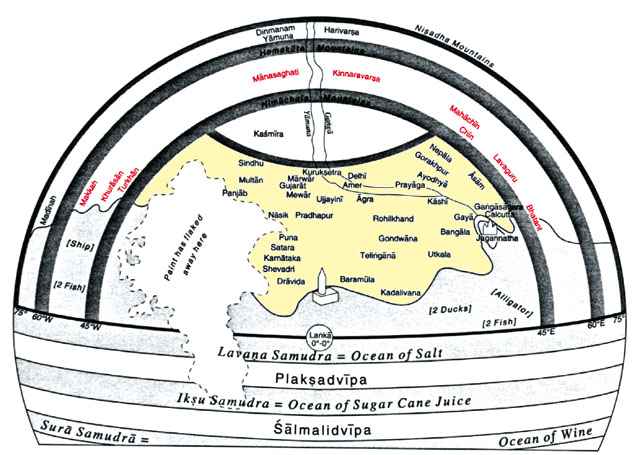

Six horizontal and two vertical mountain chains divide Jambudvipa into nine regions, or varshas (Figure 11). The southernmost region is called Bharata-varsha. Careful study shows that this map corresponds to India plus adjoining areas of south-central Asia. The first step in making this identification is to observe that the Bhagavatam assigns many rivers in India to Bharata-varsha. Thus Bharata-varsha represents India. The same can be said of many mountains in Bharata-varsha. In particular, the Bhagavatam places the Himalayas to the north of Bharata-varsha in Jambudvipa (Figure 11).

Six horizontal and two vertical mountain chains divide Jambudvipa into nine regions, or varshas (Figure 11). The southernmost region is called Bharata-varsha. Careful study shows that this map corresponds to India plus adjoining areas of south-central Asia. The first step in making this identification is to observe that the Bhagavatam assigns many rivers in India to Bharata-varsha. Thus Bharata-varsha represents India. The same can be said of many mountains in Bharata-varsha. In particular, the Bhagavatam places the Himalayas to the north of Bharata-varsha in Jambudvipa (Figure 11).

A detailed study of Puranic accounts allows the other mountain ranges of Jambudvipa to be identified with mountain ranges in the region north of India. Although this region includes some of the most desolate and mountainous country in the world, it was nonetheless important in ancient times. For example, the famous Silk Road passes through this region. The Pamir mountains can be identified with Mount Meru and Ilavrita-varsha, the square region in the center of Jambudvipa. (Note that Mount Meru does not represent the polar axis in this interpretation.)

Other Puranas give more geographical details that support this interpretation.

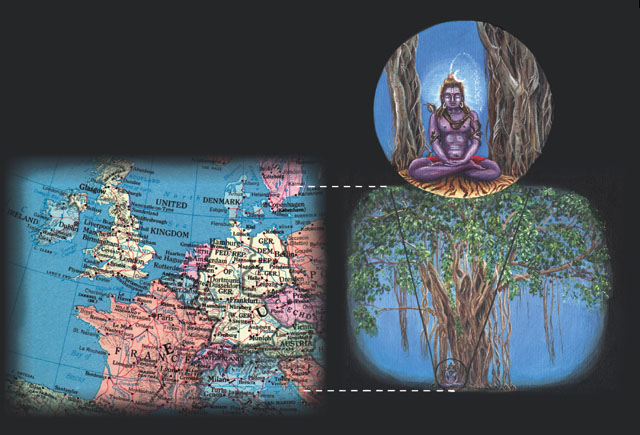

| (4) Bhu-mandala as a Map of the Celestial Realm of the Devas |

People in India in ancient times used to go in pilgrimage on foot from one end of India to the other, so they knew how large India is. Why does the Bhagavatam give such unrealistic distances? The answer is that Jambudvipa doubles as a model of the heavenly realm, in which everything is on a superhuman scale. The Bhagavatam portrays the demigods and other divine beings that inhabit this realm to be correspondingly large. Figure 12 shows Lord Siva in comparison with Europe, according to one text of the Bhagavatam.

Figure 13

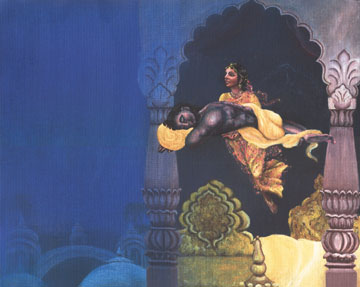

Why would the Bhagavatam describe Jambudvipa as both part of the earth and part of the celestial realm? Because there’s a connection between the two. To understand, let’s consider the idea of parallel worlds. By siddhis, or mystic perfections, one can take shortcuts across space. This is illustrated by a story from the Bhagavatam in which the mystic yogini Citralekha abducts Aniruddha from his bed in Dvaraka and transports him mystically to a distant city (Figure 13).

Why would the Bhagavatam describe Jambudvipa as both part of the earth and part of the celestial realm? Because there’s a connection between the two. To understand, let’s consider the idea of parallel worlds. By siddhis, or mystic perfections, one can take shortcuts across space. This is illustrated by a story from the Bhagavatam in which the mystic yogini Citralekha abducts Aniruddha from his bed in Dvaraka and transports him mystically to a distant city (Figure 13).

Besides moving from one place to another in ordinary space, the mystic siddhis enable one to travel in the all-pervading ether or to enter another continuum. The classical example of a parallel continuum is Krishna’s transcendental realm of Vrindavana, said to be unlimitedly expansive and to exist in parallel to the finite, earthly Vrindavana in India.

Figure 14 |

|

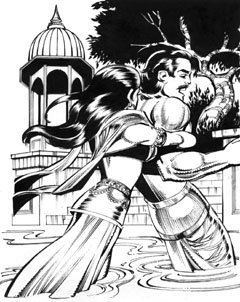

The Sanskrit literature abounds with stories of parallel worlds. For example, the Mahabharata tells the story of how the Naga princess Ulupi abducted Arjuna while he was bathing in the Ganges River (Figure 14). Ulupi pulled Arjuna down not to the riverbed, as we would expect, but into the kingdom of the Nagas (celestial snakelike beings), which exists in another dimension.

Mystical travel explains how the worlds of the devas are connected with our world. In particular, it explains how Jambudvipa, as a celestial realm of devas, is connected with Jambudvipa as the Earth or part of the Earth. Thus the double model of Jambudvipa makes sense in terms of the Puranic understanding of the siddhis.

Concluding Observations:

The Vertical Dimension in Bhagavata Cosmology

Last updated on March 5, 2002.

© 2004 Govardhan Hill Publishing